Beside a faded 19th-century portrait hangs a fresh, contemporary face. The same arch of the brow, a similar gleam in the eyes—after generations, a bloodline can leave such a distinct imprint on a face. British photographer Drew Gardner spent fifteen years completing this visual dialogue across time.

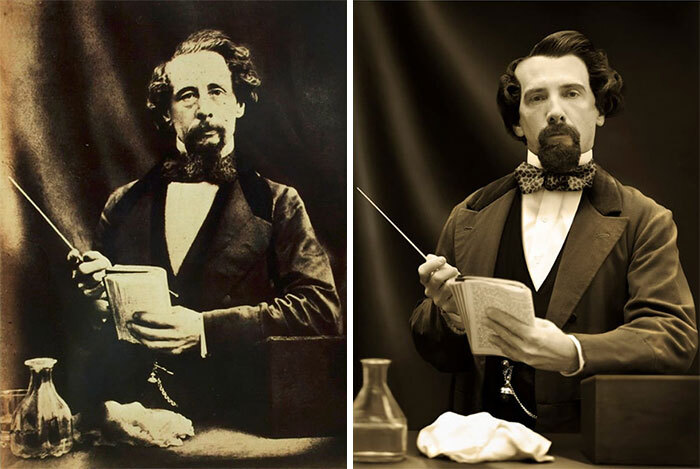

The great-great-grandson of literary giant Charles Dickens retains the family’s signature beard and profound gaze. Dressed in vintage attire and holding a book, he seems as if the author of Oliver Twist has stepped from the past. Helen Pankhurst, the great-granddaughter of suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst, inherits her grandmother’s resolute eyes, continuing the mission to advocate for gender equality. This portrait is not merely a replication of appearance but a transmission of spirit.

The Origin: A Question Spanning Generations

“You look so much like him.” These words, spoken casually by his mother fifteen years ago, planted a seed in Gardner’s mind. If resemblances exist between grandparents and grandchildren in ordinary families, could the faces of those who shaped history also flow quietly through the genes of their descendants?

This question gave birth to the series “The Descendants.” Gardner chose not to make simple physical comparisons but embarked on a meticulous artistic archaeology: each subject had to be a direct descendant of a historical figure, and each work had to meticulously recreate the lighting, posture, and even the texture of the clothing from the original portrait.

The Search: Tracing Bloodlines Through Historical Dust

The search itself became part of the creation. Gardner traced family lineages online, collaborated with professional genealogists, and scoured museum archives for clues. Once a subject was identified, communication often began with an email and gradually extended into conversations lasting weeks or even years. He believed that only by truly understanding his subjects could he capture those fleeting nuances, the essence possibly inherited from their ancestors.

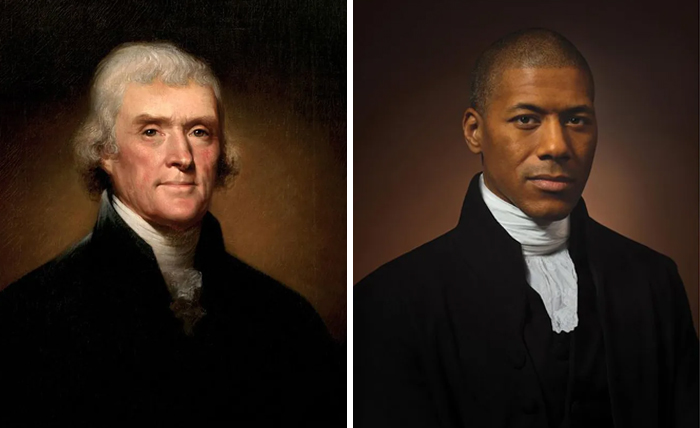

To find a descendant of the Mona Lisa, he traveled through Tuscany, Italy, eventually locating two 15th-great-granddaughters who run a vineyard. Shannon LaNier, the sixth-great-grandson of U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, initially refused to be photographed. As a descendant of Jefferson and his enslaved mistress Sally Hemings, LaNier held complex feelings toward his ancestor. After multiple conversations, he agreed to participate but refused to wear a wig, insisting on maintaining his own identity.

The Replication: Utmost Respect for Historical Detail

When photographing Napoleon’s descendant, Gardner borrowed an antique military uniform similar to the one in the painting. To recreate Dickens’s portrait, he studied the lighting techniques of mid-19th century London studios. Each garment required sourcing period-accurate fabrics; every prop had to be historically verified; each beam of light was adjusted repeatedly until it perfectly mirrored the shadows in the original portrait. This dedication to detail created a remarkable resonance between two moments separated by a century in the lens.

Recreating the portrait of a Mona Lisa descendant took a full two years from research to completion. The chair and table in the background were custom-made, and the carpenter was specially commissioned. Gardner meticulously analyzed the lighting of each original portrait, patiently replicating it using various equipment and techniques. When certain elements no longer existed, he recreated them physically or digitally.

“Sometimes, looking through the viewfinder, I’d just freeze,” Gardner described his experience during shoots. When the descendant of the Duke of Wellington tilted his head slightly, or when the great-granddaughter of suffragist leader Emmeline Pankhurst looked directly into the lens, an indescribable sense of familiarity would quietly emerge. Yet he always remained restrained, never pointing out specific resemblances—”I leave the judgment entirely to the viewer.”

The Portraits: A Dialogue of Faces Across Centuries

Lisa del Giocondo (subject of the Mona Lisa) and 15th-Great-Granddaughter Irina Guicciardini Strozzi

Gardner spent two full years searching and preparing to complete this comparative portrait.

Napoleon (1812) and Fourth-Great-Grandson Hugo de Salis

The same fringe, similar eye sockets—as if the military genius’s blood still flows in his descendant.

Thomas Jefferson (1800) and Sixth-Great-Grandson Shannon LaNier

As one of America’s Founding Fathers, the contrast between Jefferson and his Black descendant prompts profound reflection on the history of slavery in the United States.

Charles Dickens (1858) and Great-Great-Grandson Gerald Charles Dickens

The same hairstyle and beard, a similar demeanor—it’s as if the literary giant has traveled through time.

Emmeline Pankhurst and Great-Granddaughter Helen Pankhurst

The features of this British suffragette leader are clearly continued in her descendant.

More Historical Figures and Their Descendants:

• Oliver Cromwell (1653-1654) and Charles Bush

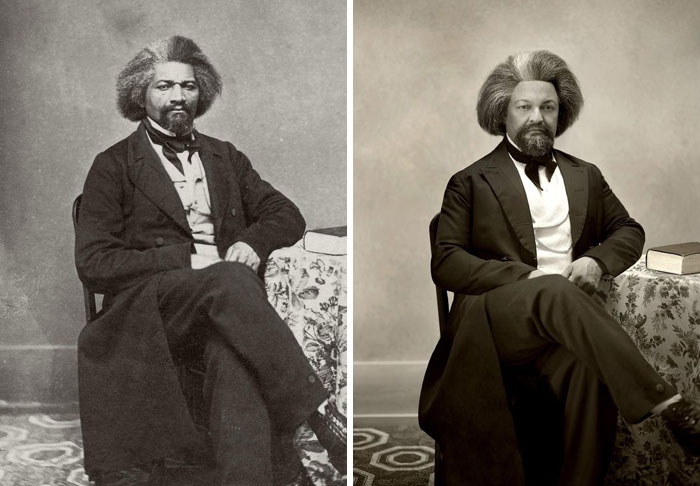

• Frederick Douglass (1863) and Reuben L. Andrews

• Charles II (1653) and Lord Charles FitzRoy

• Arthur Wellesley (1st Duke of Wellington) and Jeremy Clyde

• William Wordsworth (1798) and Andtó Wootton

• Horatio Nelson (1800) and William John Raglan

The Dialogue: Historical Echoes Beyond Bloodlines

The discussions sparked by these juxtaposed portraits extend far beyond physical appearance. The contrast between Thomas Jefferson and his descendant leads people to re-examine that complex history; the descendant of Mona Lisa model Lisa del Giocondo brings a Renaissance face into the present day. Each paired portrait is like a window. Through the heritage of bloodlines, we are allowed to gaze upon history from a more human perspective.

In an era where digital replication is increasingly prevalent, Gardner chose the most traditional approach—seeking genuine bloodline connections, patiently building human understanding, and carefully recreating historical scenes—to complete this visual experiment about time, heredity, and memory. He not only recreates the faces of historical figures but also rekindles public interest in history.

Those facial contours, still recognizable across centuries, and those expressions quietly passed down through bloodline, seem to remind us: history has never truly faded away. It resides in the contours of our eyes, in every unconscious expression, quietly awaiting the moment to be awakened.

Earlier ArtThat was honored to be invited by 19M under Chanel to engage in this dialogue with the participating artists Simone Pheuplin and Julian Farade:”A New Interpretation Of ‘Home Philosophy’ In Cross-Cultural Dialogue“, hoping to seek new interpretations through @喜可贺’s “Chinese Home Philosophy for a New Lifestyle”, reflect on the universal value of “home” as a carrier of cultural memory and emotion.

Which historical figure and descendant pairing moves you the most? Feel free to share your thoughts. For more works, visit: drewgardner.com