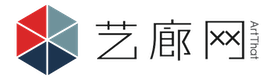

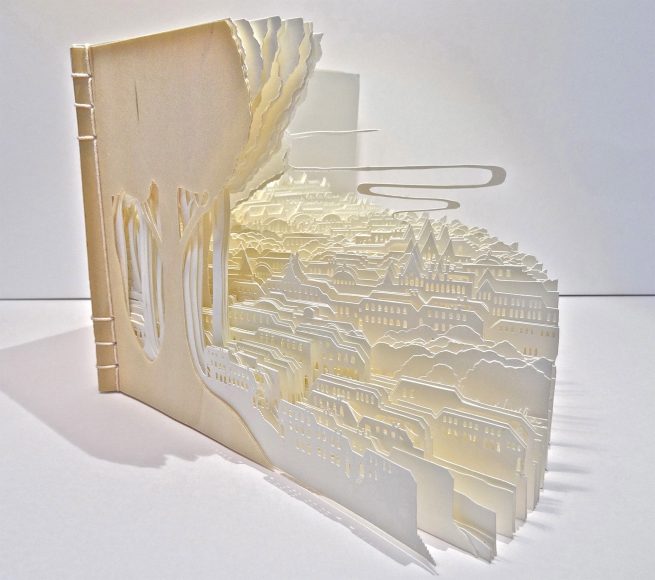

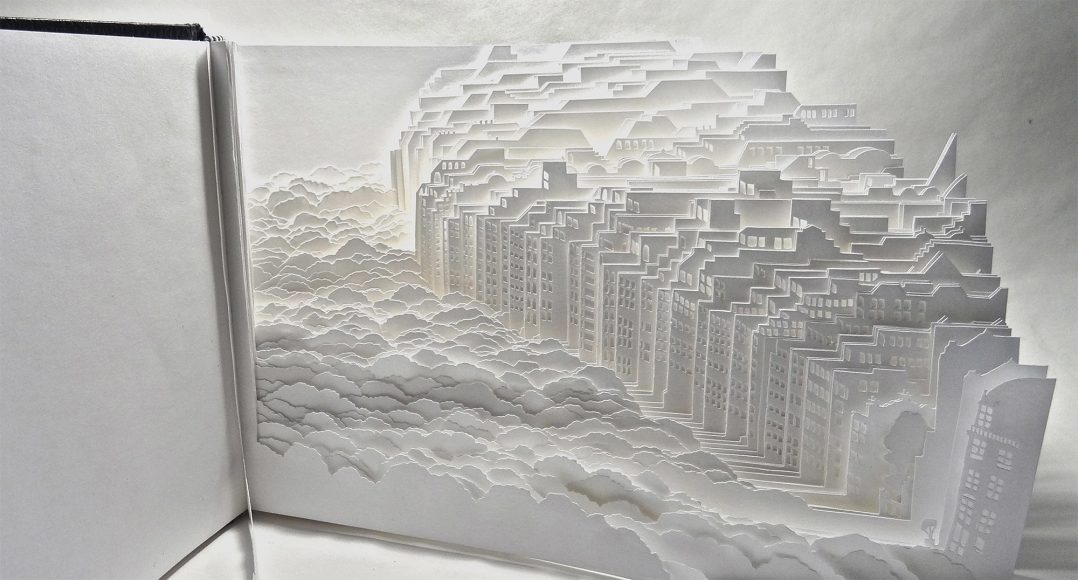

Inside a glass case lit by sunlight, a forest stands in quiet grace—carved from dozens of layers of paper. Looking closer, one can see winding paths, interlaced branches, and tiny houses nestled among the trees. All of this is born from the hands of Japanese artist Ayumi Shibata.

Ayumi Shibata never begins with a pencil outline. This is not only because paper cannot withstand repeated erasures, but also stems from her unique creative process—she visualizes the three-dimensional form in her mind and starts cutting directly.

To her, light and shadow, front and back, yin and yang are like two sides of the same coin—an integral whole. By not relying on sketches, every cut becomes an irreversible moment, infusing her work with an improvisational poetry and a sense of breath.

Micro and Macro: Seeing Worlds Inside and Outside Glass

Shibata’s artistic philosophy is deeply rooted in a remarkable linguistic connection: in Japanese, the word for “paper” (紙, kami) shares its pronunciation with the word for “god” or “spirit” (神, kami). This is not merely phonetic coincidence but forms the spiritual core of her art.

She sees paper not only as a material but as something that carries the meaning of “deity,” “divinity,” or “the spirit of nature.” Through carving paper, she seeks to touch a presence beyond the visible—those natural spirits we cannot see but may encounter, converse with, and coexist alongside.

These paper cutting works, unfolded within books or under small domes, represent what she calls the “microcosm”—symbolizing our human society, the Earth, and even broader universes and multiple dimensions.

Paper as a Bridge Connecting Humans and Nature

In her choice of materials, she consistently uses only paper. This not only echoes the cultural metaphor of “paper as spirit” but also reflects her contemplation on modern life: in an age of increasing artificiality, the original and subtle connection between humans and nature feels ever more precious.

With extreme patience, she carves and stacks dozens of paper layers, building scenes that are both delicate and grand. The process itself is like a focused meditation. The fragility and resilience of paper aptly mirror the delicate relationship between humanity and natural forces—one of both dependence and reverence.

Ayumi Shibata does not attempt to provide clear answers through her work. Instead, she uses paper, light, and shadow to create an accessible, contemplative space—a place where viewers can pause from the rhythm of daily life, sense a quiet presence, and reconsider their own connection to nature and to the unspeakable “spirit.”

In your view, can art serve as a bridge between the “visible” and the “invisible”? Feel free to share your reflections in the comments.